What was Khartoum like? Well, I enjoyed it enough and felt safe enough there that I decided to stay a few extra days and take the train to Wadi Halfa on the Egyptian border to meet up with the rest of the group. The people were overwhelmingly friendly (after visiting a food stand twice I would be greeted as an old friend), the city quite modern (fastest Internet since South Africa hands down), the street food superb (I lived off of shwarmas, falafel, and fresh fruit juice), and there were hardly any beggers or touts around (a relief after Ethiopia). Khartoum is billed as the safest major city in Africa, and I believe it.

Of course, it is also a police state, make no mistake about it, and the omnipresent soldiers and cops keep tight control. Homeless and beggars are "moved," and shantytowns of internally displaced people that spring up around the edges of Khartoum are regularly razed. Chalk it up to healthy paranoia, but I would be willing to bet that a few people who talked to me did so for routine surveillance purposes. Tourists were few and far between, after all -- I may have seen one white person a day outside of areas where the expats lived and worked.

Some allowances, however, are made for foreigners living in Khartoum. I went to the home of some UN workers one night and was amazed to see a fully stocked bar in one room. Alcohol is forbidden, but the government apparently turns a blind eye to expats who bring alcohol into the country. They are allowed to drink and have a party in their own homes, although if any local Sudanese people happen to be in attendance the police will raid the party and only the locals punished. I had a beer, feeling all the while like I was in a Prohibition style speakeasy.

Although Sudan is a strict Muslim country with a huge police presence, there is a pleasantly vast array of people in Khartoum. Emma and I sat outside of one of my favorite food stands for awhile watching the human parade, and both of us were struck by the unexpected variety of dress. Women swathed all in black with only their eyes showing floated by other women in European style skirts mincing along in heels. There were mothers constantly adjusting their traditional, brilliantly colored fabrics wrapped artfully around their bodies walking with their teenage daughters attired in long jean skirts and daringly showing some hair under their headscarves. The same spectrum of dress from traditional to modern also applied to the men, but the contrast was more startling in the women.

Because of oil, Khartoum is developing fast. The Chinese are building and paving roads through Sudan, Ethiopia, and possibly into Kenya to assist in eventual export of Sudan's oil. Large luxury hotels are springing up in anticipation of businessmen and wealthy tourists; companies such as Adidas are opening large stores; upscale bakeries and ice cream shops are full of both expat and rich local customers (one place called Ozone would be a hit anywhere in the world, and had some of the best cheesecake and ice cream I have ever tasted). I talked with one man on the street who had recently returned to Khartoum after being a professor in Malaysia for over 10 years and I expressed amazement at the wealth I saw around. He said that it was all new, mostly within the past year.

I couldn't help but wonder what effect the prosperity might have on the country. The northern and southern portion of Sudan are strongly divided, and there is an upcoming referendum in 2011 in which the south will vote whether or not to join the north. It will likely lead to full-blown civil war because it all boils down to control of oil reserves. However, will the newfound wealth have any type of mitigation effect? Will it influence the outcome in a positive or negative manner? Will there be enough other nations with vested interests at that point to broker peaceful resolutions? Unfortunately, I think the picture is pretty bleak.

Despite the nascent prosperity, Sudan retains a healthy, Byzantine system of rules and regulations when it comes to government offices. For example as a foreign tourist, one is required to register within three days of entry into the country. We all chose to go the morning after we arrived in Khartoum, thinking we would be finished within a couple of hours and be on our way. Talk about a misguided assumption. First, we spent a couple of hours trying to find the correct place because, as we discovered, the offices had moved. Countless accosted locals and wrong turns later, we finally blundered upon a building with the words "Alien Registration" on a placard outside the surrounding rock wall topped by concertina wire. The crowd inside was either shoving and shouting or standing on the sidelines with set looks of resignation on their faces. It was a daunting hive of activity precisely because there was absolutely no order or process for registering. It seems none of the officials knew what was going on, either. We rushed from office to office, some repeatedly, throwing elbows at people who were trying to elbow their way past us, getting chided by police -- and that was just to obtain the registration form. At one point, a soldier took pity on Mike, Matt, and me, guiding us to a room in which a woman stapled our forms and pictures neatly in a folder. Finally! Progress! He then ushered us to another jam packed room where a fellow presided imperiously over one corner, wielding a stamp and a look of constant distain. We presented our neatly packaged registration forms only to have him wave his hand dismissively. An Arabic argument of epic proportions ensued between stamp wielder, his presumed lackey, and the soldier of goodness, while Mike, Matt, and I watched bemusedly. Eventually, the soldier rushed us back to the room with the stapler woman, first consulting with another woman who immediately started castigating the soldier while repeatedly slapping the folder with no small amount of force. The stapler woman finally ripped our forms out of the folder (presumably at the other woman's direction) and handed our torn forms back to us. The soldier of goodness then shepherded us back to Mr. Imperious Stamp Wielder, who, after more arguing with our soldier guardian while peering at us coldly over the top of his glasses, finally pompously stamped our forms. With successfully stamped forms in hand we joined the scrum outside trying to pay for the privilege of registering as an alien. Upon successfully fighting through the jostling horde and making it to the payment window (a few of us banded together and formed a human wall so that others could not reach through the window), one had to scream and wave money in order to get an official's attention who would actually take the money and passport. It was as if they couldn't be asked and needed to finish smoking their cigarette first. It is the rare government office that does not take one's money at the drop of the hat. And God forbid you didn't have exact change. After finally getting someone to take the registration money, it was time to wait. And wait. And wait. I think it was about three hours before we eventually received our passports containing our coveted alien registration stamp (luckily, there was a fantastic shawarma place around the corner). Six hours had passed since we had walked into the building.

Emma, Matt, and I had a similar experience with the train. A train ride seemed like a pleasant, peaceful method of transport north through the desert, and we had decided to give it a go. The train runs once a week to the Egyptian border for the express purpose of meeting the Lake Nasser ferry which is the only method of transport between Sudan and Egypt. The journey by train is 36 hours versus up to a week by car. Easy decision, right? Nothing runs very smoothly in Africa, though, especially Sudan. We had all budgeted to leave Khartoum on Monday and made it to the train station with little cash to spare. As our 8:30 a.m. departure time came and went, it became clear that something was wrong. We pieced together that the ferry had been cancelled for a maintanence check and so the train had also been cancelled. No need to run the train if the ferry wasn't on schedule, after all. After several hours, the powers that be decided the train would run on Wednesday which, if everything went smoothly, would get us to the border with one day to spare before our visas expired. With basically no money in our pockets and nowhere to stay, we hiked back to our campsite some five kilometers away across the Nile, which isn't very far until you try to carry bags that distance in 100 degree heat -- including one which we took turns balancing on our heads.

Once back at the campsite we had to figure out how to get money. Because of American sanctions, there was no way for me to use my ATM or credit card in Sudan and I had left them on the truck. No ATMs accept foreign bank cards, anyway, and basically dollars are the preferred type of currency one can exchange at banks. None of us had any dollars to spare (rookie mistake), and Matt and Emma only had enough Sudanese Pounds to pay for themselves at the border. We had heard of places that might be able to do cash advances on Matt's credit card, but it was certainly not common knowledge. So we embarked on a quest to find one of these fabled businesses. We figured Western Union would be a good bet, or at least might know something, but once we found them (a quest in and of itself) they were completely useless. We tried a couple more banks before hitting upon one where the bank manager had a friend who might be able to arrange something for us. After a few minutes he emerged from his office and said "Come with me, I take you," and he drove us in his car (in which I spent a few uncomfortable minutes in the passenger seat non-commitally listening to him go on a tirade against Americans while Matt and Emma, both from England, tried unsuccessfully to muffle their laughter in the back seat) to an Indian hotel where we were swept into the manager's office. Yes, it was true that he sometimes did cash advances on credit cards of up to $500 dollars for some of his guests, and he could probably do the same for us. We exchanged glances and started raving about the smells of Indian food coming from the kitchen, saying we were starving and had been craving Indian food and was it too late to have lunch there? That seemed to be a good enough trade-off for the manager, and he handed Matt a form to fill out which he subsequently faxed to an office in Saudi Arabia that processed the cash advance. Once the transaction had been accepted, the Saudi Arabia office called back the manager with the ok and he paid out crisp US dollars to Matt. Cash in hand, we promptly spent the majority of it on the Indian lunch.

We made it to the train station without incident Wednesday and saw with delight that the train was at the station. We piled into our first class cabin compartment to find peeling paint, the most uncomfortable seats in the world, and that only two of the six seat backs were actually fastened to the wall -- the other four required an engineering degree to keep balanced on the seat without falling to the ground. It was a dusty, uncomfortable, bustling train ride featuring random stops of indeterminate length (one had to be ready to sprint to the train because it would give one toot with the horn and start rolling about 8.4 seconds later), spectacular scenery, and the loudest tea and coffee hawker ever (he repeatedly popped into our compartment until we bought from him). One needs a permit to take pictures in Sudan and even then there is a laundry list of things one cannot photograph -- everything from bridges to cripples. I didn't have a permit so the train was my only chance to take photos, and even then I had to be careful of the soldiers. In fact, Emma got in trouble when she took a seemingly innocuous scenery photo. Regardless, I managed to get a few shots out the window.

At some points it seemed like a donkey would been faster than the train. Especially when we stopped once for 8 hours (!):

The entire length of the Nile is cultivated:

The entire length of the Nile is cultivated: A man selling candied dates at one of the train stops. I bought nearly 5 pounds worth for $2:

A man selling candied dates at one of the train stops. I bought nearly 5 pounds worth for $2: Random fellows on the train:

Random fellows on the train: Boy from the neighboring compartment that had recently discovered how to make farting noises. Some things are truly cross-cultural...:

Boy from the neighboring compartment that had recently discovered how to make farting noises. Some things are truly cross-cultural...: Tuckered out:

Tuckered out: Impish smile:

Impish smile: The scene at Station 6, a few buildings in the middle of nowhere that seem to exist only for the train:

The scene at Station 6, a few buildings in the middle of nowhere that seem to exist only for the train: Lining up for food:

Lining up for food:

Lonely view at Station 6:

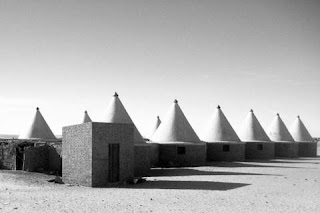

Lonely view at Station 6: Interesting buildings outside of Station 6. No idea what they are for, but they looked cool:

Interesting buildings outside of Station 6. No idea what they are for, but they looked cool: Shadow of a couple of roof riders. Apparently it is free if you ride on the roof, but not sure how they manage to stay on because the roof is curved, there are no handles, and the train is quite possibly the bumpiest on the planet:

Shadow of a couple of roof riders. Apparently it is free if you ride on the roof, but not sure how they manage to stay on because the roof is curved, there are no handles, and the train is quite possibly the bumpiest on the planet: Dejected donkey:

Dejected donkey:

Me, Matt, and a whole lotta desert:

Emma accepts a bet on how much of her body she can get outside the train:

Emma accepts a bet on how much of her body she can get outside the train: Sunset on Lake Nasser

Sunset on Lake Nasser